Werner van Rossum is a senior finance and enterprise transformation leader with experience leading large-scale initiatives at the intersection of data, technology, and performance management in complex global organizations. His work has focused on enterprise finance transformation, including reporting and analytics modernization, integrated operating model design, data harmonization, and decision-support capabilities.

With a global career spanning Europe, the Middle East, and the United States, Werner has led multi-year finance and performance management transformations in highly complex environments, aligning planning, governance, and analytics capabilities to support executive decision-making at scale. His experience includes enterprise FP&A modernization, S/4HANA finance transformation, and the design of data foundations supporting advanced analytics and AI-enabled decision support.

Werner contributes professional thought leadership on topics including enterprise finance transformation, performance management, data strategy, and governance in large organizations.

Additional background and selected publications are available at https://v-rossum.com

| Werner van Rossum | Points |

|---|---|

| Academic | 42 |

| Author | 15 |

| Influencer | 16 |

| Speaker | 13 |

| Entrepreneur | 30 |

| Total | 116 |

Points based upon Thinkers360 patent-pending algorithm.

Tags: Change Management, Leadership, Personal Branding

Tags: Business Strategy, Change Management, Leadership

Master of Science - MS, International Business - Accounting and Finance

Master of Science - MS, International Business - Accounting and Finance

Tags: Finance, GRC, Transformation

Tags: Finance, GRC, Management

Tags: Finance, Leadership, Transformation

Tags: Finance, Leadership, Transformation

Why Analytics Breaks During System Transformations - And How to Design for Continuity

Why Analytics Breaks During System Transformations - And How to Design for Continuity

Tags: Analytics, Digital Disruption, Transformation

When Governance Slows Decisions: Rethinking Control, Materiality, and Trust

When Governance Slows Decisions: Rethinking Control, Materiality, and Trust

Tags: Finance, GRC, Transformation

Designing FP&A for Decision Advantage: A Framework for Processes, Systems, and Skills at Enterprise Scale

Designing FP&A for Decision Advantage: A Framework for Processes, Systems, and Skills at Enterprise Scale

Tags: Digital Transformation, Finance, Transformation

When Planning Detail Starts to Undermine Strategy

When Planning Detail Starts to Undermine Strategy

Tags: Digital Transformation, Finance, Transformation

Outcome-Driven Planning: How Global Enterprises Can Align Business Plans With Strategy

Outcome-Driven Planning: How Global Enterprises Can Align Business Plans With Strategy

Tags: Digital Transformation, Finance, Transformation

The Clarity Crisis: The Anatomy of a High Impact Financial Story

The Clarity Crisis: The Anatomy of a High Impact Financial Story

Tags: Digital Transformation, Finance, Transformation

The Clarity Crisis: The Anatomy of a High-Impact Financial Story

The Clarity Crisis: The Anatomy of a High-Impact Financial Story

Tags: Business Strategy, Finance, Transformation

The Clarity Crisis: Why Modern Finance Is Drowning in Data but Starving for Insight

The Clarity Crisis: Why Modern Finance Is Drowning in Data but Starving for Insight

Tags: Digital Transformation, Finance, Transformation

Turning Data Into Decisions: The Art of Finance Storytelling

Turning Data Into Decisions: The Art of Finance Storytelling

Tags: Digital Transformation, Finance, Transformation

Tags: Transformation

Business Venture Manager - Performance Management (Plan to Perform)

Business Venture Manager - Performance Management (Plan to Perform)

Tags: Digital Transformation, Finance, Transformation

Tags: Digital Transformation, Finance, Transformation

Tags: Digital Transformation, Finance, Transformation

Tags: Digital Transformation, Finance, Transformation

Tags: Digital Transformation, Finance, Transformation

Tags: Digital Transformation, Finance, Transformation

Tags: Digital Transformation, Leadership, Transformation

Tags: Digital Transformation, Finance, Transformation

Tags: Finance, GRC, Transformation

Tags: Transformation

Tags: Digital Transformation, Finance, Transformation

Why Governance Needs Two Standards of Rigor

Why Governance Needs Two Standards of Rigor

Many executives describe the same frustration in different words. Decisions take longer than they should, even when the direction seems clear. Forecasts are refined again. Variances are reconciled one more time. Assumptions are revisited until confidence feels complete.

Governance is often blamed, vaguely, for this slowdown. Yet governance itself is rarely the real problem. The issue is more subtle. Most organizations operate with two fundamentally different governance objectives, but treat them as if they were the same.

In most large organizations, one form of governance dominates almost by default: financial statement integrity governance. Its purpose is to protect external stakeholders by ensuring that reported results are accurate, consistent, and compliant with applicable standards. This form of governance is necessarily conservative, retrospective, and intolerant of error. Its rigor is non-negotiable.

Alongside it sits a second, equally legitimate objective: decision governance. The purpose of decision governance is to enable timely, well-informed management decisions under uncertainty. It is forward-looking by design. Rather than attempting to eliminate uncertainty, it seeks to surface it, bound it, and make it actionable.

Both forms of governance are essential. Problems arise when they are implicitly treated as interchangeable.

This distinction can be formalized as a dual-rigor governance model. Financial statement integrity governance and decision governance serve different purposes, operate on different time horizons, and require different standards of precision. The former is designed to ensure reliability, comparability, and compliance in externally reported results. The latter is designed to support timely managerial judgment under uncertainty. Treating these objectives as interchangeable creates predictable failure modes, including excessive reconciliation, false precision, and delayed action. Recognizing governance as purpose-specific rather than monolithic allows rigor to be applied proportionally, preserving control where accuracy is essential while enabling speed and judgment where direction and risk awareness matter more than exactness.

In many organizations, the standards designed to safeguard external reporting quietly migrate into internal decision forums. Forecasts are expected to converge as tightly as reported results. Immaterial differences trigger reconciliation. Residual uncertainty becomes a reason to delay rather than an input to judgment.

This feels responsible. It looks disciplined. But it introduces a mismatch between what decisions actually require and what governance implicitly demands.

Decisions rarely require reporting-grade precision. They require directional confidence, understanding of trade-offs, and clarity on risk exposure. When decision readiness becomes tied to the level of assurance appropriate for external reporting, speed suffers without a corresponding improvement in decision quality.

This dynamic is most visible during enterprise planning and forecasting cycles, when forecast accuracy is still improving but decision windows are already closing. In those moments, additional precision does little to change direction, while delay materially changes outcomes.

It is tempting to frame this dynamic as overcontrol or excessive conservatism. In practice, it is neither.

Most controls were introduced for good reasons. Audit findings, regulatory expectations, and past errors all leave behind governance artifacts that accumulate over time. Rarely are these controls removed once the original concern has passed.

The failure is not one of intent, but of design. Governance systems drift toward protecting what already exists because that objective is measurable and defensible. Creating new value, by contrast, requires judgment under uncertainty and acceptance of bounded risk.

When governance is not explicitly calibrated to the type of decision being made, organizations default to the safest standard available. That standard is usually financial reporting rigor.

Organizations that explicitly distinguish decision governance from financial statement integrity governance behave differently.

They define materiality thresholds for decision contexts rather than inheriting reporting tolerances. They make uncertainty visible and assign ownership instead of reconciling it away. They accept that some numbers need to be directionally right rather than mechanically precise.

This does not weaken control. It strengthens it by aligning rigor with purpose. External reporting remains uncompromised. Decision processes become faster and more effective because governance is designed to support action rather than delay it.

This distinction has direct implications for how finance and analytics operate.

When decision-grade analytics is tightly coupled to general ledger structures or transactional systems, every change propagates reconciliation pressure into decision forums. Materiality collapses. Precision escalates by default.

Separating decision analytics from systems of record, often through stable semantic layers, allows governance to focus on relevance and insight rather than mechanical accuracy. Finance teams spend less time explaining immaterial differences and more time helping leaders understand trade-offs, sensitivities, and implications.

Good governance is not about eliminating risk or perfecting numbers. It is about creating the conditions for sound judgment.

Organizations that move faster are not reckless. They are clearer. Clearer about which governance objective applies. Clearer about what level of accuracy is sufficient. Clearer about where uncertainty must be managed rather than removed.

When governance is designed with that clarity, it stops being a brake on decision-making and becomes what it was always meant to be: an enabler of responsible action.

I explore the distinction between decision governance and financial statement integrity governance in more depth in a recent article published in The European Financial Review.

Tags: Digital Transformation, Finance, Transformation

Why Enterprise Analytics Fail When They Are Designed Around Tools Instead of Decisions

Why Enterprise Analytics Fail When They Are Designed Around Tools Instead of Decisions

Enterprise analytics programs rarely fail in visible or dramatic ways. Dashboards are delivered, data pipelines run reliably, and reporting volumes increase. Yet executive decision forums continue to rely on offline analyses, parallel models, or informal narratives. The analytics function appears productive, but its influence on actual decisions remains limited.

This pattern reflects a design inversion. Most analytics architectures are optimized for analytic reuse and technical scalability rather than for decision resolution. As a result, they perform well on their own terms while remaining institutionally peripheral.

Most enterprise analytics environments evolve along one of two design paths.

The first is ERP-centric. Analytics are treated as an extension of transactional systems, with reporting layered directly on top of operational data structures. Fidelity to source systems becomes the organizing principle, and alignment with transactional definitions is treated as analytical rigor.

The second is analytics-centric. A dedicated analytics stack is introduced, emphasizing reusable datasets, standardized metrics, and self-service exploration. Architectural success is measured by coverage, consistency, and adoption of common definitions.

Despite their technical differences, both paths share a critical limitation. They organize analytics around systems, datasets, and abstractions rather than around decision accountability. Metrics are defined because they are computable, reusable, and scalable, not because they resolve a specific managerial choice.

The result is a familiar paradox. Analytics outputs are internally coherent and technically robust, yet only loosely connected to the decisions that govern resource allocation, risk acceptance, and performance commitments.

When analytics adoption disappoints, organizations frequently respond by embedding analytics more deeply into operational tools. KPIs are surfaced inside ERP transactions. Dashboards are integrated into daily workflows. Alerts are automated and pushed to users.

At limited scale, this can improve visibility. At enterprise scale, it often produces the opposite effect.

Embedded analytics multiply exposure to metrics without clarifying decision rights. Users encounter indicators without knowing whether they are expected to interpret them, escalate them, or act on them. Authority remains implicit, while information becomes pervasive.

Over time, analytics are experienced less as decision support and more as ambient signal. Metrics compete with operational priorities rather than guiding them. The failure is not one of access or latency, but of institutional design. Information is present everywhere, yet responsibility is nowhere.

A related failure mode lies in how analytics are constructed.

In many organizations, business logic is defined directly within dashboards. Measures are shaped to fit visual layouts. Calculations are duplicated across reports to meet local needs. This coupling accelerates delivery and creates visible progress.

The long-term cost is architectural fragility. When definitions change, impacts are difficult to trace. When a metric must support a different decision forum, it must be recreated rather than reused. Governance discussions collapse into technical debates because there is no stable, decision-level logic layer to interrogate.

More importantly, tightly coupled analytics do not scale with decision maturity. As organizations evolve, decisions increasingly involve trade-offs, constraints, and scenarios rather than single metrics. Architectures optimized for static visualization struggle to support deliberation, comparison, and commitment.

A decision-centered approach reverses the typical design sequence.

Instead of starting with data sources or tools, it begins with governance forums. These are the recurring settings in which the organization commits resources, revises expectations, or accepts risk. Examples include forecast reviews, capital allocation committees, performance reviews, and risk governance councils.

For each forum, the design questions are explicit:

Analytics are then designed only to the extent required to support those judgments. Metrics exist because they differentiate between alternatives. Scenarios exist because choices exist. Visualizations are shaped to support deliberation and resolution, not exploration in the abstract.

This approach deliberately constrains analytics. It reduces metric proliferation, limits ad hoc definition changes, and resists universal self-service. Those constraints are not incidental. They are what allow analytics to remain stable, governable, and trusted within decision forums over time.

Analytics architectures that sustain decision relevance tend to share several characteristics.

They separate decision logic from presentation. Definitions, assumptions, and thresholds are governed independently of how they are visualized or delivered.

They privilege decision stability over data exhaustiveness. Only information that materially affects outcomes is surfaced, even when additional data is readily available.

They align data refresh cycles with decision cadence. Real-time data is used where real-time decisions exist. Elsewhere, consistency and interpretability take precedence over immediacy.

They treat analytics as institutional infrastructure rather than informational output. Metrics are durable, traceable, and auditable because decisions rely on them repeatedly, not episodically.

Underlying these choices is a different premise. Analytics is not primarily an information problem. It is a decision system design problem. Tools enable that system, but they do not define it.

Enterprise analytics rarely fail because the numbers are wrong. They fail because they are successful on their own terms while remaining disconnected from the decisions that govern the enterprise.

Designing analytics backward from decisions does not simplify the work. It narrows it. That narrowing forces clarity about what matters, who decides, and why the analysis exists at all.

For organizations seeking durable value from analytics, that constraint is not a limitation. It is the architectural choice that determines whether analytics remain peripheral or become institutionally consequential.

Tags: Digital Transformation, Finance, Transformation

Why FP&A Breaks at Scale - and How to Design It for Decision Advantage

Why FP&A Breaks at Scale - and How to Design It for Decision Advantage

In many large organizations, FP&A is expected to do more than ever before. Beyond budgeting and variance analysis, it is asked to support strategy execution, inform capital allocation, and provide forward-looking insight in increasingly volatile environments.

Yet at enterprise scale, the outcome is often paradoxical.

Despite heavy investment in tools, data platforms, and reporting capabilities, FP&A teams frequently find themselves overwhelmed by volume rather than empowered by clarity. Analysts spend significant time reconciling numbers, explaining discrepancies, and preparing extensive materials, while senior leaders receive more information than they can realistically absorb or act on. The result is a function that is operationally busy, yet strategically constrained.

In my experience, this is rarely a talent problem or a technology problem. More often, it is a design problem.

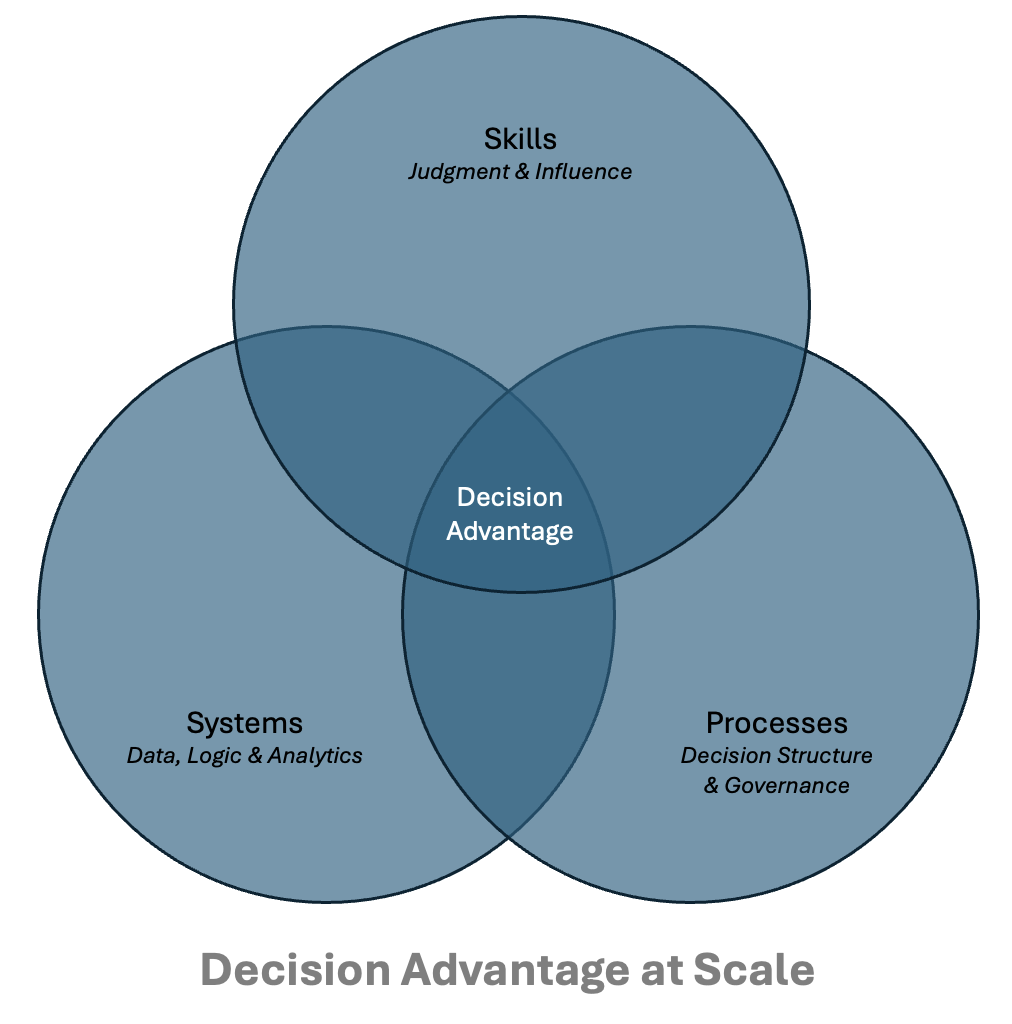

This article builds on my recent publication in the World Financial Review, where I introduced an integrated framework for designing Financial Planning & Analysis (FP&A) as a source of decision advantage at enterprise scale. Here, I expand on the practical implications of that framework and explore why traditional FP&A models tend to break down as organizations grow in size and complexity.

A recurring issue in large FP&A organizations is that success is implicitly measured by analytical sophistication or reporting completeness. More models, more scenarios, more dashboards are assumed to equate to better decisions.

In practice, that assumption often fails.

What ultimately matters is not how much analysis is produced, but whether insight reaches decision-makers in time, with credibility, and in a form that is directly relevant to the decision at hand. I refer to this capability as decision advantage.

Decision advantage is not synonymous with forecasting accuracy or advanced analytics. Highly accurate forecasts that arrive after decisions are locked in, or insights that are not trusted due to inconsistent definitions, do little to shape outcomes. At scale, decision advantage emerges only when information production is intentionally linked to decision execution.

Viewing FP&A through a decision-advantage lens shifts the transformation question. Instead of asking how to optimize individual components, the focus becomes how to design FP&A as an integrated enterprise capability.

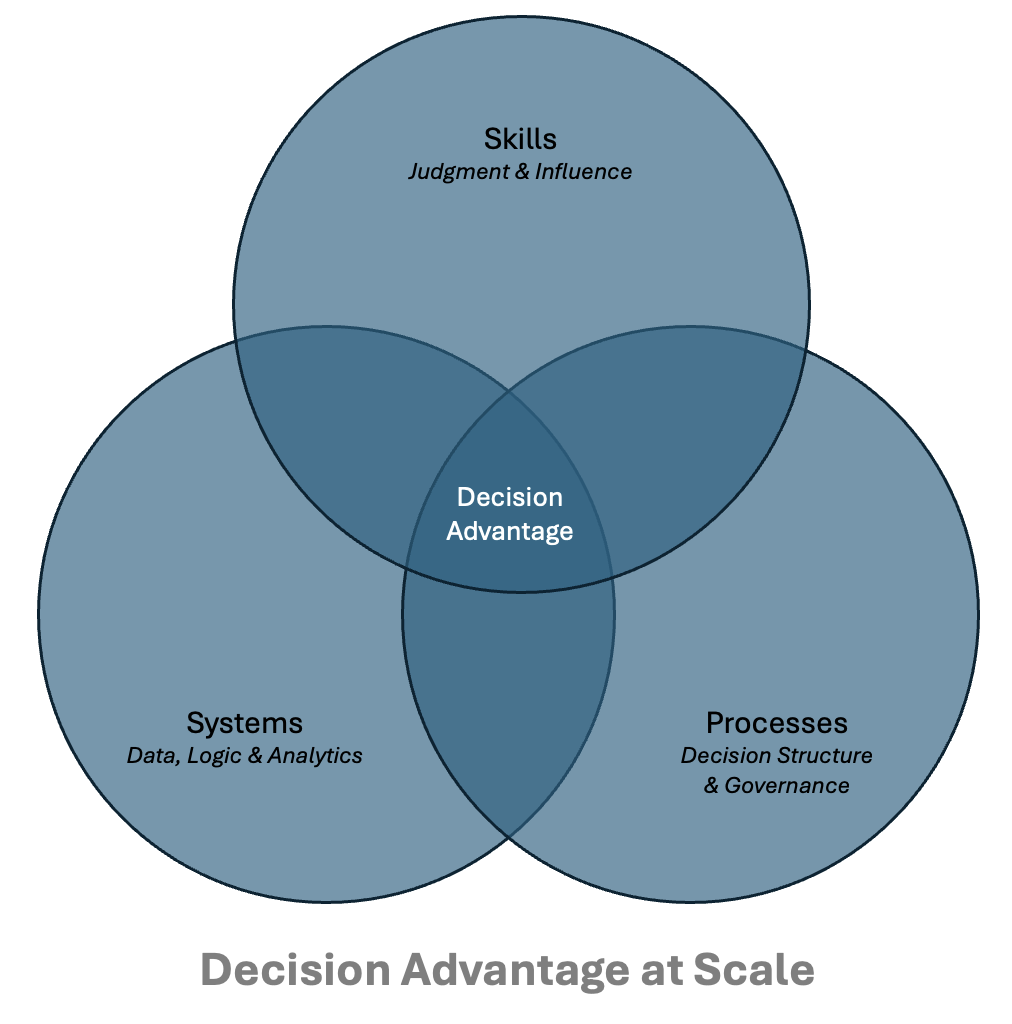

I find it useful to frame this design challenge around three interdependent pillars:

Processes - how decisions are structured, sequenced, and governed

Systems - how data, calculation logic, and analytics are enabled and scaled

Skills - how people interpret information, exercise judgment, and influence outcomes

At enterprise scale, none of these elements can be optimized in isolation. Improving tools without redesigning decision processes often shifts effort from analysis to reconciliation. Standardizing processes without investing in professional judgment increases control at the expense of insight. Developing talent without fixing system fragmentation limits impact.

Decision advantage emerges only when these pillars are deliberately aligned.

As organizations grow larger and more complex, decision latency and fragmentation tend to increase. Governance layers multiply, local requirements accumulate, and analytical effort drifts toward explaining the past rather than shaping future choices. What works in a single business unit rarely scales cleanly across a global, multi-business enterprise.

Designing FP&A for decision advantage is therefore not a technical exercise. It is a leadership choice about what the organization chooses to plan, measure, review, and escalate - and just as importantly, what it chooses to stop doing.

For a deeper, structured treatment of this framework, the full article is available via the World Financial Review: Designing Enterprise FP&A for Decision Advantage - The World Financial Review

Tags: Digital Transformation, Finance, Transformation

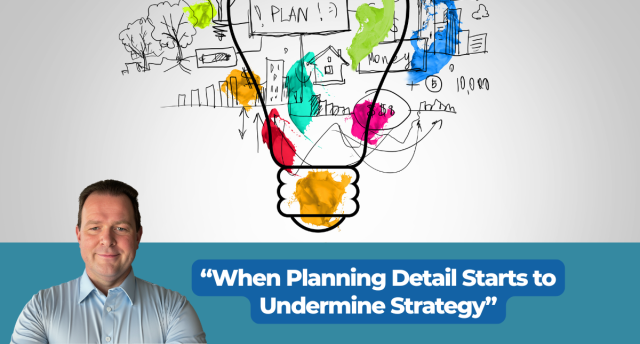

When Planning Detail Starts to Undermine Strategy

When Planning Detail Starts to Undermine Strategy

In many organizations, planning gradually shifts from a strategy-led exercise to a detailed operational negotiation. As assumptions multiply and templates expand, strategic intent remains referenced but no longer leads decision-making.

This article examines why excessive detail introduced too early can undermine strategy, how planning processes often conflate long-term strategic alignment with short-term operational accuracy, and why effective planning works in the opposite order. It also explores how digital transformation, when grounded in clear strategic anchors and sound data foundations, can support better planning by enabling faster scenario analysis without accelerating confusion.

The organizations that plan well are not those with the most granular forecasts, but those that preserve strategic clarity throughout the planning process, using detail to inform decisions rather than replace them.

Tags: Digital Transformation, Finance, Transformation

Data Isn’t the Problem. Alignment Is.

Data Isn’t the Problem. Alignment Is.

Many organizations believe they have a data problem. In reality, they have an alignment problem.

I’ve seen companies invest heavily in modern platforms, dashboards, and analytics - yet still struggle to make timely decisions. The issue isn’t data quality or technology capability. It’s that each function defines success differently.

Real transformation happens when organizations move to a single performance model: one KPI framework, one source of truth, and one shared interpretation.

When alignment replaces fragmentation, decision velocity increases more than any additional technology investment ever could.

Tags: Digital Transformation, Finance, Transformation

Strategy Fails When It Becomes a Spreadsheet Exercise

Strategy Fails When It Becomes a Spreadsheet Exercise

A lot of organizations think they have a strategy issue, but more often it’s a planning issue.

If your annual plan starts with last year’s numbers, you’re already negotiating against your own ambition.

When planning turns into a routine of templates, historical run rates, and incremental tweaks, strategy quietly moves to the background.

Outcome-driven planning changes that. Start with the outcomes you actually want, agree on the few decisions that matter, and build the plan around those choices.

It sounds simple, but it forces clarity and real alignment. Most importantly, it keeps leaders focused on where the business needs to go — not where it happened to be last year.

Tags: Digital Transformation, Finance, Transformation

Location: Virtual, in person globally Fees: By invitation

Service Type: Service Offered

Why Governance Needs Two Standards of Rigor

Why Governance Needs Two Standards of Rigor Why Enterprise Analytics Fail When They Are Designed Around Tools Instead of Decisions

Why Enterprise Analytics Fail When They Are Designed Around Tools Instead of Decisions Why FP&A Breaks at Scale - and How to Design It for Decision Advantage

Why FP&A Breaks at Scale - and How to Design It for Decision Advantage