Feb06

Many executives describe the same frustration in different words. Decisions take longer than they should, even when the direction seems clear. Forecasts are refined again. Variances are reconciled one more time. Assumptions are revisited until confidence feels complete.

Governance is often blamed, vaguely, for this slowdown. Yet governance itself is rarely the real problem. The issue is more subtle. Most organizations operate with two fundamentally different governance objectives, but treat them as if they were the same.

In most large organizations, one form of governance dominates almost by default: financial statement integrity governance. Its purpose is to protect external stakeholders by ensuring that reported results are accurate, consistent, and compliant with applicable standards. This form of governance is necessarily conservative, retrospective, and intolerant of error. Its rigor is non-negotiable.

Alongside it sits a second, equally legitimate objective: decision governance. The purpose of decision governance is to enable timely, well-informed management decisions under uncertainty. It is forward-looking by design. Rather than attempting to eliminate uncertainty, it seeks to surface it, bound it, and make it actionable.

Both forms of governance are essential. Problems arise when they are implicitly treated as interchangeable.

This distinction can be formalized as a dual-rigor governance model. Financial statement integrity governance and decision governance serve different purposes, operate on different time horizons, and require different standards of precision. The former is designed to ensure reliability, comparability, and compliance in externally reported results. The latter is designed to support timely managerial judgment under uncertainty. Treating these objectives as interchangeable creates predictable failure modes, including excessive reconciliation, false precision, and delayed action. Recognizing governance as purpose-specific rather than monolithic allows rigor to be applied proportionally, preserving control where accuracy is essential while enabling speed and judgment where direction and risk awareness matter more than exactness.

In many organizations, the standards designed to safeguard external reporting quietly migrate into internal decision forums. Forecasts are expected to converge as tightly as reported results. Immaterial differences trigger reconciliation. Residual uncertainty becomes a reason to delay rather than an input to judgment.

This feels responsible. It looks disciplined. But it introduces a mismatch between what decisions actually require and what governance implicitly demands.

Decisions rarely require reporting-grade precision. They require directional confidence, understanding of trade-offs, and clarity on risk exposure. When decision readiness becomes tied to the level of assurance appropriate for external reporting, speed suffers without a corresponding improvement in decision quality.

This dynamic is most visible during enterprise planning and forecasting cycles, when forecast accuracy is still improving but decision windows are already closing. In those moments, additional precision does little to change direction, while delay materially changes outcomes.

It is tempting to frame this dynamic as overcontrol or excessive conservatism. In practice, it is neither.

Most controls were introduced for good reasons. Audit findings, regulatory expectations, and past errors all leave behind governance artifacts that accumulate over time. Rarely are these controls removed once the original concern has passed.

The failure is not one of intent, but of design. Governance systems drift toward protecting what already exists because that objective is measurable and defensible. Creating new value, by contrast, requires judgment under uncertainty and acceptance of bounded risk.

When governance is not explicitly calibrated to the type of decision being made, organizations default to the safest standard available. That standard is usually financial reporting rigor.

Organizations that explicitly distinguish decision governance from financial statement integrity governance behave differently.

They define materiality thresholds for decision contexts rather than inheriting reporting tolerances. They make uncertainty visible and assign ownership instead of reconciling it away. They accept that some numbers need to be directionally right rather than mechanically precise.

This does not weaken control. It strengthens it by aligning rigor with purpose. External reporting remains uncompromised. Decision processes become faster and more effective because governance is designed to support action rather than delay it.

This distinction has direct implications for how finance and analytics operate.

When decision-grade analytics is tightly coupled to general ledger structures or transactional systems, every change propagates reconciliation pressure into decision forums. Materiality collapses. Precision escalates by default.

Separating decision analytics from systems of record, often through stable semantic layers, allows governance to focus on relevance and insight rather than mechanical accuracy. Finance teams spend less time explaining immaterial differences and more time helping leaders understand trade-offs, sensitivities, and implications.

Good governance is not about eliminating risk or perfecting numbers. It is about creating the conditions for sound judgment.

Organizations that move faster are not reckless. They are clearer. Clearer about which governance objective applies. Clearer about what level of accuracy is sufficient. Clearer about where uncertainty must be managed rather than removed.

When governance is designed with that clarity, it stops being a brake on decision-making and becomes what it was always meant to be: an enabler of responsible action.

I explore the distinction between decision governance and financial statement integrity governance in more depth in a recent article published in The European Financial Review.

Keywords: Digital Transformation, Finance, Transformation

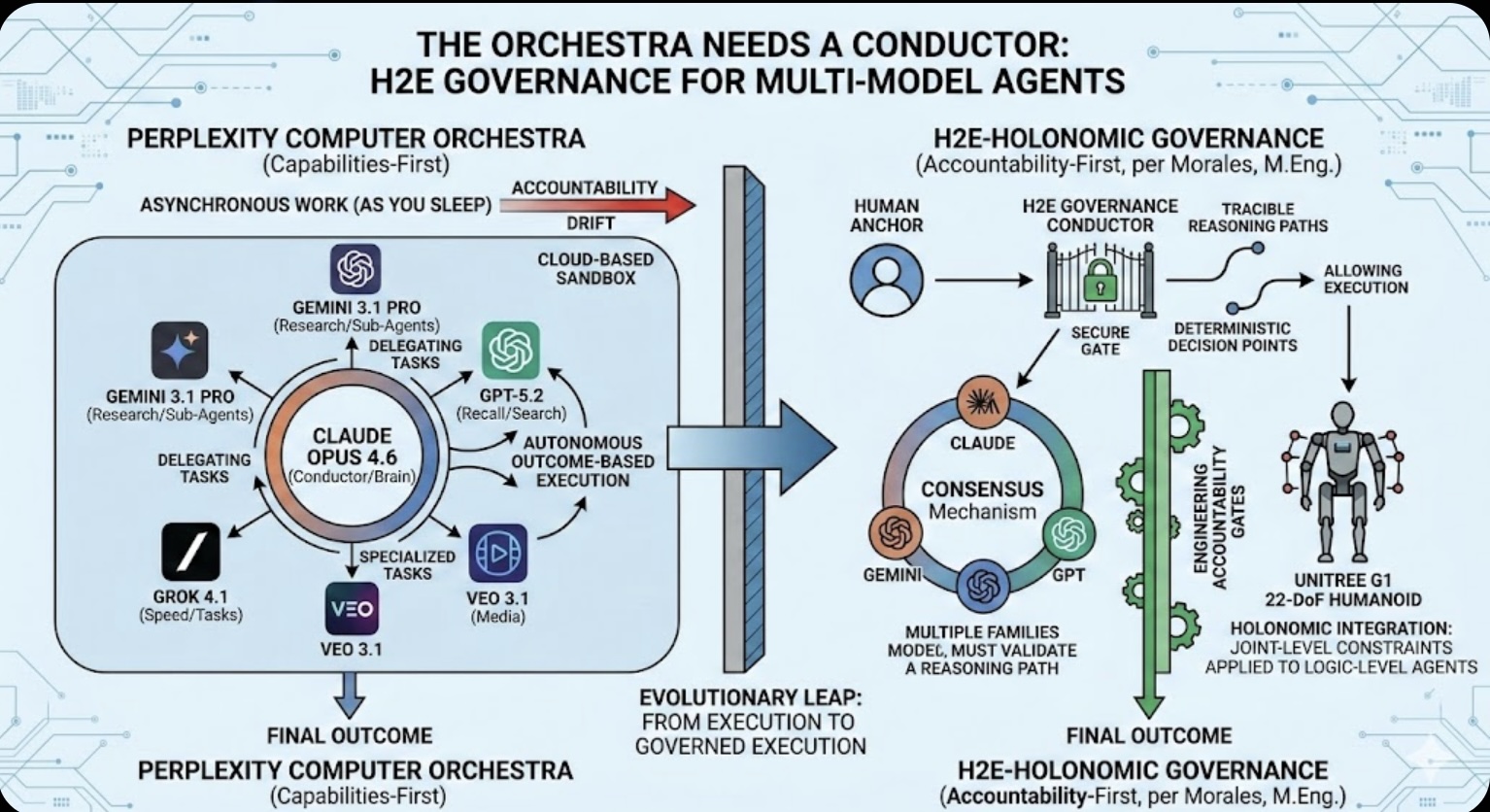

The Orchestra Needs a Conductor: Why Multi-Model Agents Require H2E Governance

The Orchestra Needs a Conductor: Why Multi-Model Agents Require H2E Governance The Role of Memory in Modern-day Business

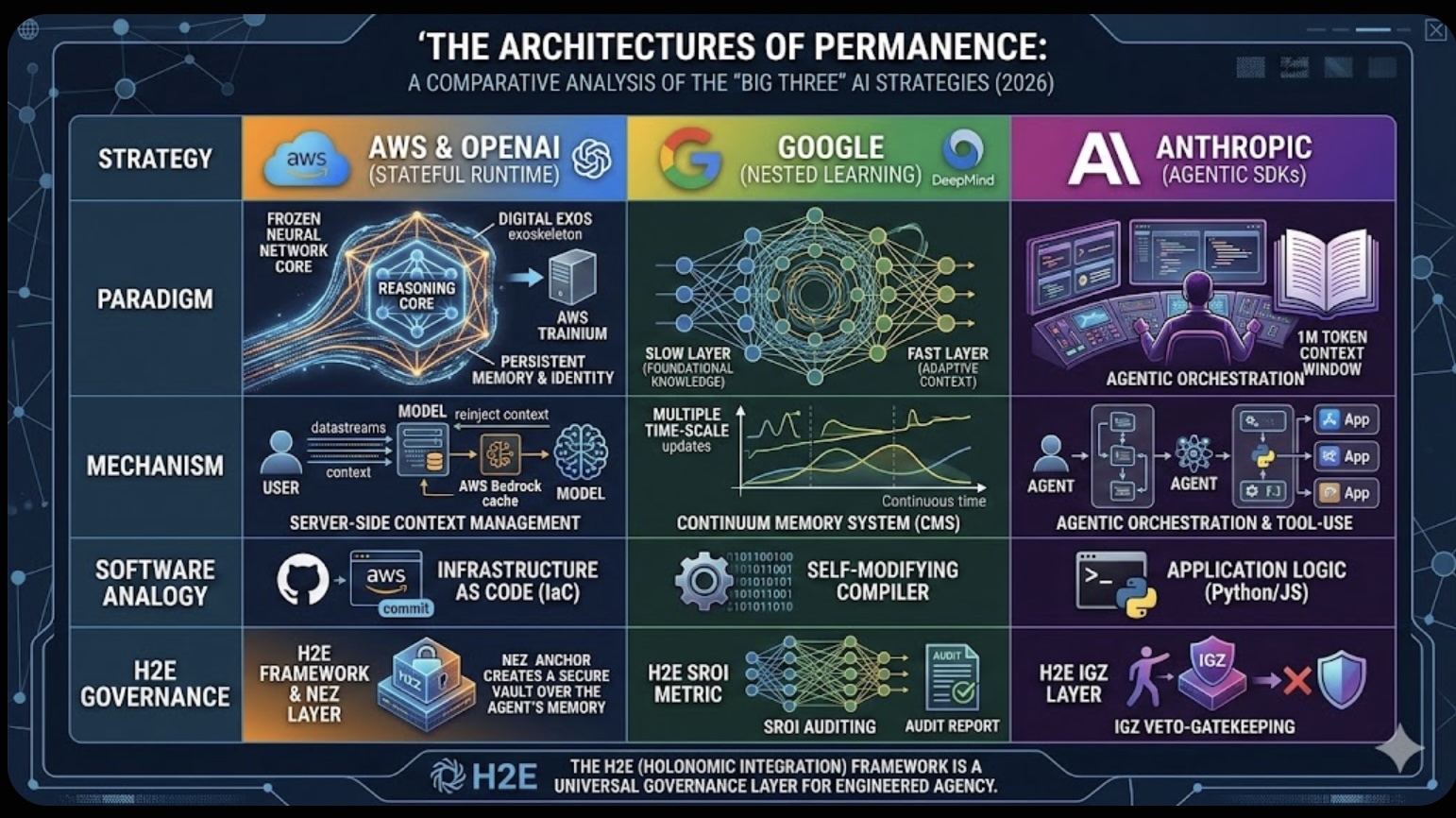

The Role of Memory in Modern-day Business The Architectures of Permanence: A Comparative Analysis of the "Big Three" AI Strategies (2026)

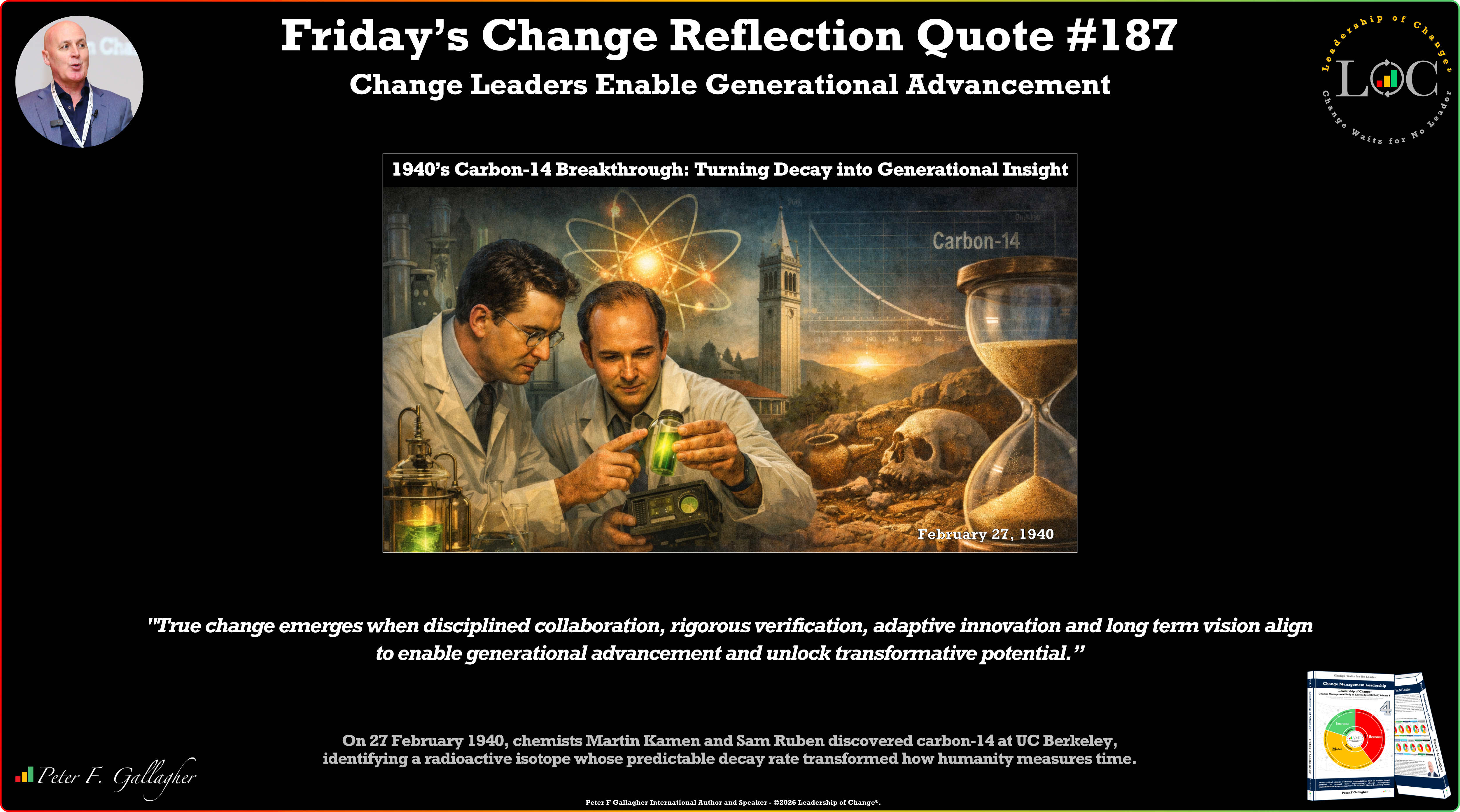

The Architectures of Permanence: A Comparative Analysis of the "Big Three" AI Strategies (2026) Friday’s Change Reflection Quote - Leadership of Change - Change Leaders Enable Generational Advancement

Friday’s Change Reflection Quote - Leadership of Change - Change Leaders Enable Generational Advancement The Corix Partners Friday Reading List - February 27, 2026

The Corix Partners Friday Reading List - February 27, 2026