Jan19

In certain parts of Europe and the US, homeowners are opening letters they didn’t expect.

Insurance renewals. Premiums up. Coverage narrowed. In some cases, quietly withdrawn. Flood risk. Heat risk. Fire risk. Pick your flavour of climate reality.

At the same time, cities are still building. More homes. More data centres. More transport infrastructure. More everything.

And almost all of it relies on the same material we’ve used, with barely a rethink, for over a century.

Concrete.

It is the backbone of modern civilisation. It is also one of climate’s least cooperative accomplices.

The construction industry is finally starting to accept that these two facts cannot coexist forever. Progress is real. But it is slow. Too slow. And the gap between what is technically possible and what is being deployed at scale is now the real problem.

This matters because concrete is not a niche issue. It is a systems issue. Climate. Security. Affordability. Resilience. All four converge here, whether the industry likes it or not.

Let’s ground this in numbers, not vibes.

According to the Global Cement and Concrete Association and reiterated by the IEA, cement and concrete account for roughly 7–8% of global CO₂ emissions. That is more than aviation and shipping combined. It is not energy use in buildings. It is the material itself.

As Ana Luisa Vaz explained on the Climate Confident podcast, producing cement emits CO₂ in two ways. First, by burning fuel at extreme temperatures. Second, and more stubbornly, through chemistry. Calcining limestone releases CO₂ by design. Even a fully electrified kiln does not solve that problem.

Globally, we pour over 30 billion tonnes of concrete every year. Urbanisation alone is expected to add the equivalent of a city the size of Paris every week through to 2050. The idea that we can decarbonise the economy while leaving concrete mostly untouched is fantasy.

Meanwhile, the built environment as a whole contributes close to 40% of global emissions when operational and embodied carbon are combined, as discussed with Tommy Linstroth in another Climate Confident episode recently. Concrete is the single largest slice of the embodied portion.

The uncomfortable truth is this. Even if we electrify everything else perfectly, cement will still blow the carbon budget unless it changes.

This is no longer an NGO talking point. It is a balance-sheet issue.

Climate: Every tonne of conventional cement locks in emissions that cannot be clawed back later. Embodied carbon is front-loaded. You emit it before the building even opens its doors.

Security: Cement supply chains are deeply exposed to geopolitics. Limestone, energy inputs, and transport all matter. As Europe learned the hard way with gas, material dependency is a strategic risk.

Affordability: Carbon pricing is no longer theoretical. EU ETS expansion, CBAM, and city-level carbon reporting rules mean embodied emissions will increasingly show up as real costs. Buildings that ignore this now will be penalised later.

Resilience: Climate stress does not just damage buildings. It stresses supply chains. Floods shut quarries. Heatwaves disrupt production. A material system that assumes stability is designing for a past that no longer exists.

This is why regulators are moving. LEED Version 5, for example, puts embodied carbon at the centre of green building standards rather than treating it as an optional extra. As Tommy Linstroth noted, you no longer “fall into” high-performance buildings by accident.

And yet, the industry response remains cautious. Conservative, even. Understandably so. When structures fail, people die. No one is asking engineers to gamble.

But safety and inertia are not the same thing.

There is no single silver bullet for concrete. Anyone selling one is selling nonsense. The pathway is plural. Messy. Incremental. But very real.

Lower-carbon concrete mixes already exist. Supplementary cementitious materials like fly ash, slag, calcined clays, and limestone fillers can reduce emissions significantly. The barrier is not physics. It is standards, procurement habits, and risk aversion.

Electrifying kilns reduces fuel emissions. It does nothing for process emissions. Both truths can coexist. Pretending otherwise wastes time.

This is where mineralisation technologies come in.

Companies like Paebbl use accelerated mineralisation to bind captured CO₂ into solid carbonates that partially replace cement. The carbon is chemically locked in, not temporarily absorbed. Buildings become storage.

Paebbl is not alone.

Different approaches. Different trade-offs. Same direction of travel.

Sensors, digital twins, and AI-assisted materials modelling are not hype here. They reduce the time it takes to prove safety, durability, and performance. As Ana Luisa Vaz described, testing cycles that once took years are being compressed dramatically.

That matters in a conservative industry. Evidence beats persuasion.

Standards must protect safety without freezing progress. That means regulators engaging earlier with material innovators, not years after deployment elsewhere. Being an enabler is now a climate strategy.

For all the frustration, the shift is underway.

Municipalities are demanding lower-carbon materials in public procurement. Developers are benchmarking embodied emissions because tenants and investors are asking. Major corporates are funding pilots, not just press releases.

Paebbl has already delivered multiple commercial pilot projects. CarbonCure concrete has been poured in tens of thousands of buildings globally. LEED Version 5 formalises what leading projects were already doing.

Perhaps most importantly, the conversation has moved.

Ten years ago, sustainable construction meant better insulation and LED lighting. Necessary, but insufficient. Today, embodied carbon is front and centre. That is progress.

It is also overdue.

Keep in mind, the concrete used in today’s buildings will still be standing when most of today’s net-zero pledges have been forgotten. Materials outlive politics. That alone should sharpen priorities.

Those insurance letters are signals, not anomalies.

They are the market pricing in physical risk faster than regulation ever could. Buildings designed without climate reality in mind are becoming liabilities, not assets.

Concrete will not disappear. Nor should it. But the way we make it must change, fast.

The construction industry is waking up. Slowly. The challenge now is not awareness. It is pace.

Because climate physics does not wait for conservative sectors to feel comfortable.

This article was originally published on TomRaftery.com

By Tom Raftery

Keywords: Climate Change, Construction, Sustainability

Lateral Moves: The Most Overlooked Succession Strategy in Companies

Lateral Moves: The Most Overlooked Succession Strategy in Companies The Asset Play: Timing, Structure & Global Arbitrage

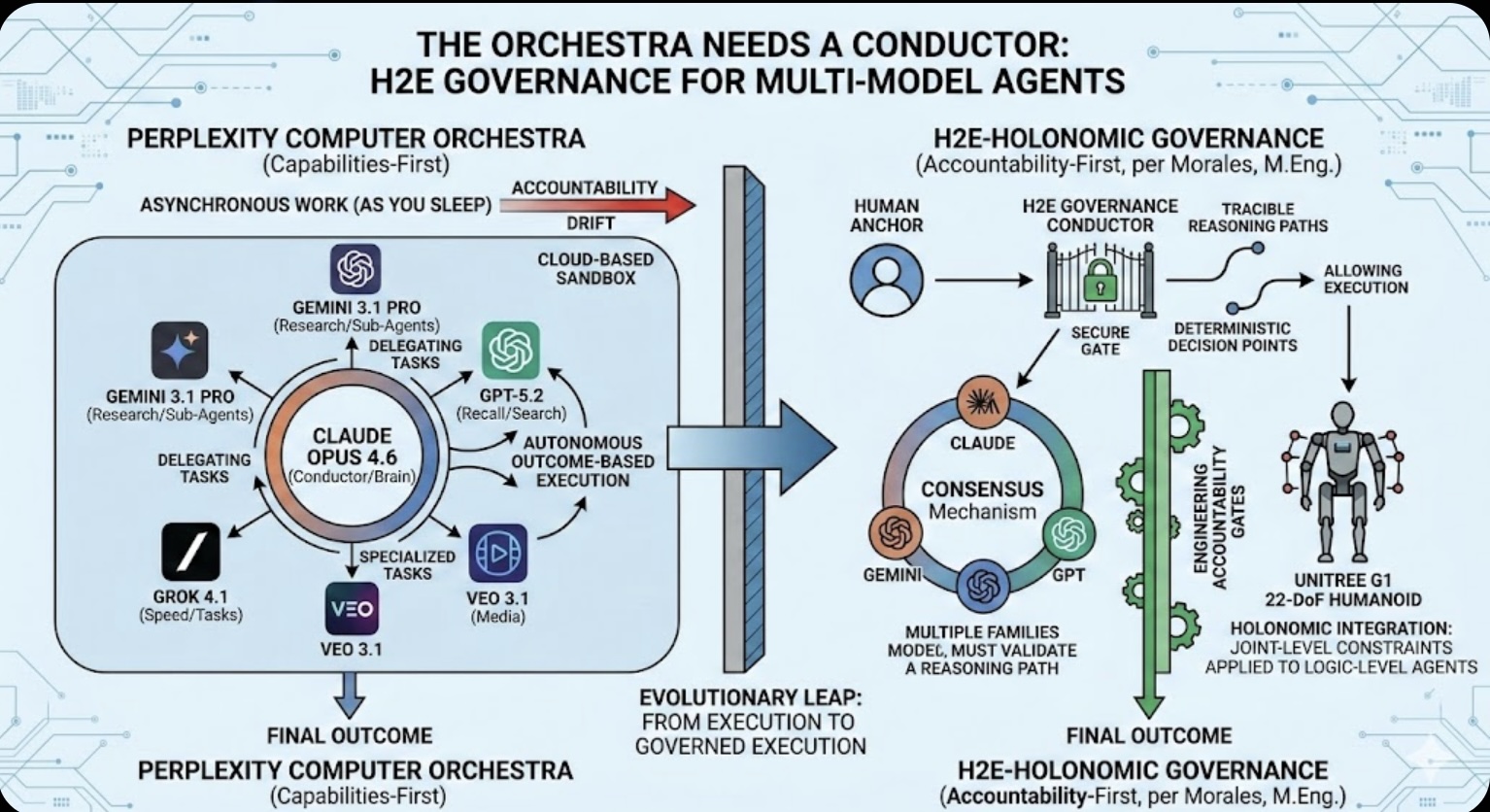

The Asset Play: Timing, Structure & Global Arbitrage  The Orchestra Needs a Conductor: Why Multi-Model Agents Require H2E Governance

The Orchestra Needs a Conductor: Why Multi-Model Agents Require H2E Governance The Role of Memory in Modern-day Business

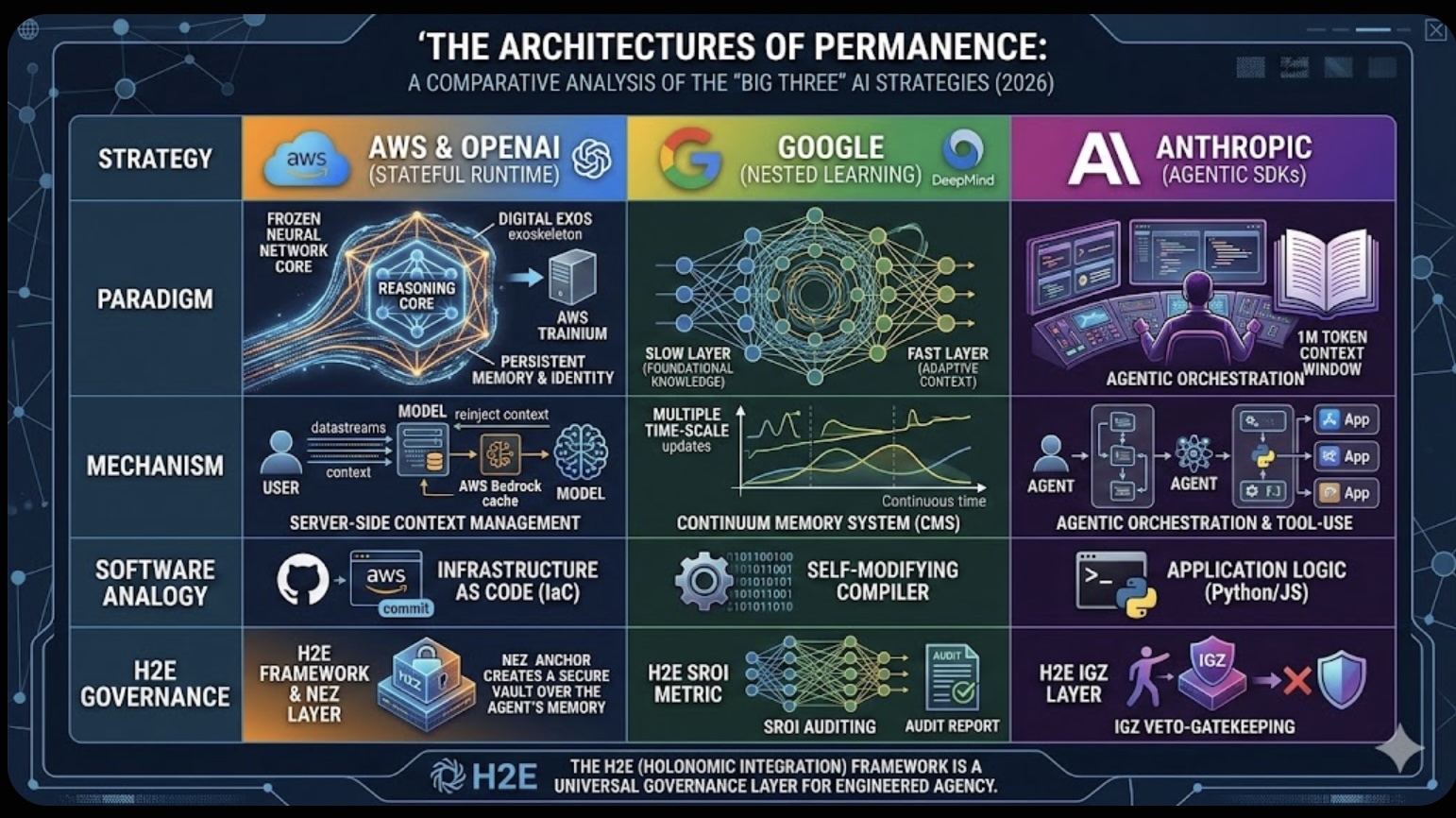

The Role of Memory in Modern-day Business The Architectures of Permanence: A Comparative Analysis of the "Big Three" AI Strategies (2026)

The Architectures of Permanence: A Comparative Analysis of the "Big Three" AI Strategies (2026)