Jan29

Last summer, in the middle of the day, wholesale electricity prices across parts of southern Europe did something that would have seemed absurd a decade ago.

They went negative.

Solar generation was surging. Rooftops, utility-scale arrays, and solar parks were all producing at once. Demand was soft. Power had nowhere useful to go. Clean electricity was curtailed because the system could not absorb it.

A few hours later, the picture flipped.

As the sun dropped, demand rose. Solar output collapsed. Gas plants ramped. Prices followed. Emissions followed too.

This is not a renewable energy problem.

It is a time problem.

For those old enough to remember TiVo, the analogy holds. Television didn’t improve because programmes suddenly got better. It improved because viewers stopped being forced to watch them live. TiVo separated production from consumption through time-shifting.

Renewable electricity is at the same point in its evolution. Solar and wind already generate vast amounts of clean power. Grids are still trying to consume it live.

Long duration energy storage (LDES) is TiVo for the power system. It lets us capture abundance and use it when it actually matters.

That is why LDES has moved from theoretical necessity to system-critical infrastructure. Not later. Now.

For more than a century, electricity systems were built on a simple assumption: supply could be controlled.

Fossil fuels made that easy. Burn more when demand rises. Throttle back when it falls. Time barely mattered.

Renewables invert the logic.

Supply becomes variable. Demand stays human. The challenge shifts from generation to coordination across time.

Short-duration (1-4 hour) lithium-ion batteries have scaled at remarkable speed. They stabilise frequency, manage ramps, and smooth short-term volatility.

But they do not bridge the midday-to-evening gap.

They do not cover multi-day weather events.

And they are not designed to operate as foundational assets for decades.

That gap is exactly where long duration energy storage now sits.

According to the IEA's 2025 Renewable Electricity Report, renewables now provide more than 32% of global electricity generation, with solar additions continuing to outpace every other technology. In many regions, solar and wind are already the cheapest new sources of power.

Yet solar still accounts for only about 5% of total global electricity generation. The constraint is no longer cost. It is usability.

As renewable penetration increases, curtailment rises and price volatility intensifies. The marginal value of short-duration storage declines unless it is paired with longer-duration solutions.

The LDES Council estimates that a cost-optimised net-zero power system requires 4–6 terawatts of long duration energy storage globally by 2030, representing a USD 3.6 trillion market and unlocking up to USD 540 billion per year in system-wide savings once deployed at scale.

That is the modelling.

Now the evidence.

In January 2026, China began operating the world’s largest compressed-air energy storage facility in Jiangsu province. The project delivers 2.4 GWh of storage, produces 600 MW of dispatchable power, and can supply electricity equivalent to 600,000 households annually. BloombergNEF describes compressed-air systems as among the most cost-effective long duration storage options available at grid scale.

This is not a pilot.

It is grid infrastructure.

California offers a complementary signal, from a different direction.

According to the California Energy Commission, the state now has 16,942 MW of installed battery storage, more than 2,100% growth since 2019, making it the second-largest storage fleet in the world after China. Roughly 13.9 GW comes from utility-scale systems, with the remainder distributed across homes, businesses, schools, and public facilities.

That build-out has materially changed grid behaviour. California has now gone three consecutive years without issuing a Flex Alert, even through record-breaking heatwaves. In 2024, the state experienced its hottest summer on record, yet the grid remained stable, supported by storage that shifted excess midday solar into the evening peak.

This matters for two reasons.

First, it decisively disproves the claim that high-renewables grids are inherently unreliable. Storage works.

Second, it exposes the next constraint. California’s battery fleet is exceptionally good at managing hours. As renewable penetration rises further, and as fossil generation continues to retire, the system will increasingly need assets that manage days and weeks, not just evenings.

In other words, batteries solved the first act of the storage problem. Long duration energy storage is the second act. Together, they form a system. Separately, they do not.

Companies such as Hydrostor, a developer of utility-scale long duration energy storage projects, are now bringing multi-gigawatt-hour facilities into operation using technologies designed for decades-long lifetimes. Alongside deployments now coming online in China, these projects reinforce the same conclusion.

LDES is no longer experimental. It is being built at scale, with economics that hold up in real power systems.

Without long duration storage, high-renewables grids remain structurally dependent on fossil backup.

Midday abundance is wasted.

Evening scarcity is fossil-fuelled.

Emissions flatten instead of falling.

LDES allows renewable electricity generated during periods of excess to displace fossil generation hours or days later. That is what turns clean power from intermittent contributor into firm backbone.

Net-zero systems do not fail at noon.

They fail after sunset.

Energy security is no longer about fuel stockpiles. It is about flexibility.

LDES converts domestic renewables into strategic assets, reducing exposure to volatile fuel markets and dampening price shocks. Grids gain autonomy over time, not just capacity.

China’s deployment pace reflects this logic. Alongside a national target of 180 GW of new energy storage capacity by 2027, its investment in multi-gigawatt-hour LDES shows a clear understanding that future power systems are defined by temporal control, not surplus generation.

Volatility is expensive. Storage reduces it.

LDES cuts system costs over the long term by reducing curtailment, stabilising wholesale prices, deferring transmission upgrades, and shrinking reliance on underutilised peaking plants.

India’s “round-the-clock” renewable tenders demonstrate this clearly. Hybrid projects combining renewables with long duration storage have cleared below the cost of new coal generation. In one 900 MW project, utilities are saving roughly USD 360 million per year compared to fossil alternatives.

This is not climate charity.

It is cost discipline.

Climate impacts are lengthening outages and deepening stress events.

LDES provides temporal resilience: multi-day backup, seasonal balancing, and the ability to absorb shocks without defaulting to diesel generation or emergency imports.

Resilient decarbonisation is not about perfection.

It is about staying functional.

Lithium-ion batteries have been transformative, but they are short-lived by infrastructure standards. Most grid-scale systems are engineered for 10–15 years, with degradation and replacement built into their economics.

LDES technologies are engineered differently.

Compressed-air systems, pumped storage variants, and thermal energy storage assets are designed for 40–60 years of operation, with refurbishable mechanical components rather than wholesale replacement.

When capital costs are amortised over decades, LDES stops looking like “expensive storage” and starts behaving like infrastructure.

Batteries optimise hours.

LDES optimises systems.

Long duration energy storage is no longer constrained by physics. It is constrained by market design.

Three regulatory nudges matter most:

1. Pay for availability, not just arbitrage

Most power markets reward short-term price spreads. That favours four-hour batteries and undervalues assets designed to deliver multi-day or seasonal value. LDES needs revenue frameworks that reward capacity, duration, and reliability.

2. Provide long-term certainty

LDES projects have long development cycles and multi-decade lifetimes. Long-term contracts, technology-neutral capacity mechanisms, and clear asset definitions reduce financing costs far more effectively than short-term incentives.

3. Plan for time explicitly

Grid planning still assumes dispatchable thermal supply. That assumption no longer holds. LDES enables transmission deferral and system optimisation, but only if it is integrated early rather than bolted on later.

China is building LDES as strategic infrastructure, prioritising scale and speed. Europe understands the system problem acutely but is slowed by fragmented markets and permitting. The United States has innovation and capital, but lacks a consistent national framework that values long-duration flexibility across regions.

The lesson is simple. The jurisdictions that align regulation with system reality first will lock in advantages that compound for decades.

LDES is no longer waiting for validation.

Compressed-air systems are operating at multi-gigawatt-hour scale. Pumped storage designs are evolving. Thermal systems are already decarbonising industrial heat.

As renewable penetration rises, costs fall, and asset lifetimes stretch across generations, the conclusion becomes unavoidable.

Long duration energy storage is not optional.

It is structural.

Back to that summer day.

At midday, clean electricity floods the grid and is thrown away.

By evening, fossil plants fill the gap.

That is the failure mode of a system without time-shifting.

LDES changes the sequence. Energy generated when it is abundant is delivered when it is scarce. Prices stabilise. Emissions fall. Grids behave.

The technology works.

The economics are lining up.

The need is accelerating.

What remains is regulatory intent.

Long duration energy storage does not make headlines when it works.

It makes systems function.

And that is why it will define the next phase of the energy transition.

This article was first published on TomRaftery.com. Photo credit Casey Fleser on Flickr

By Tom Raftery

Keywords: Climate Change, Energy, Renewable Energy

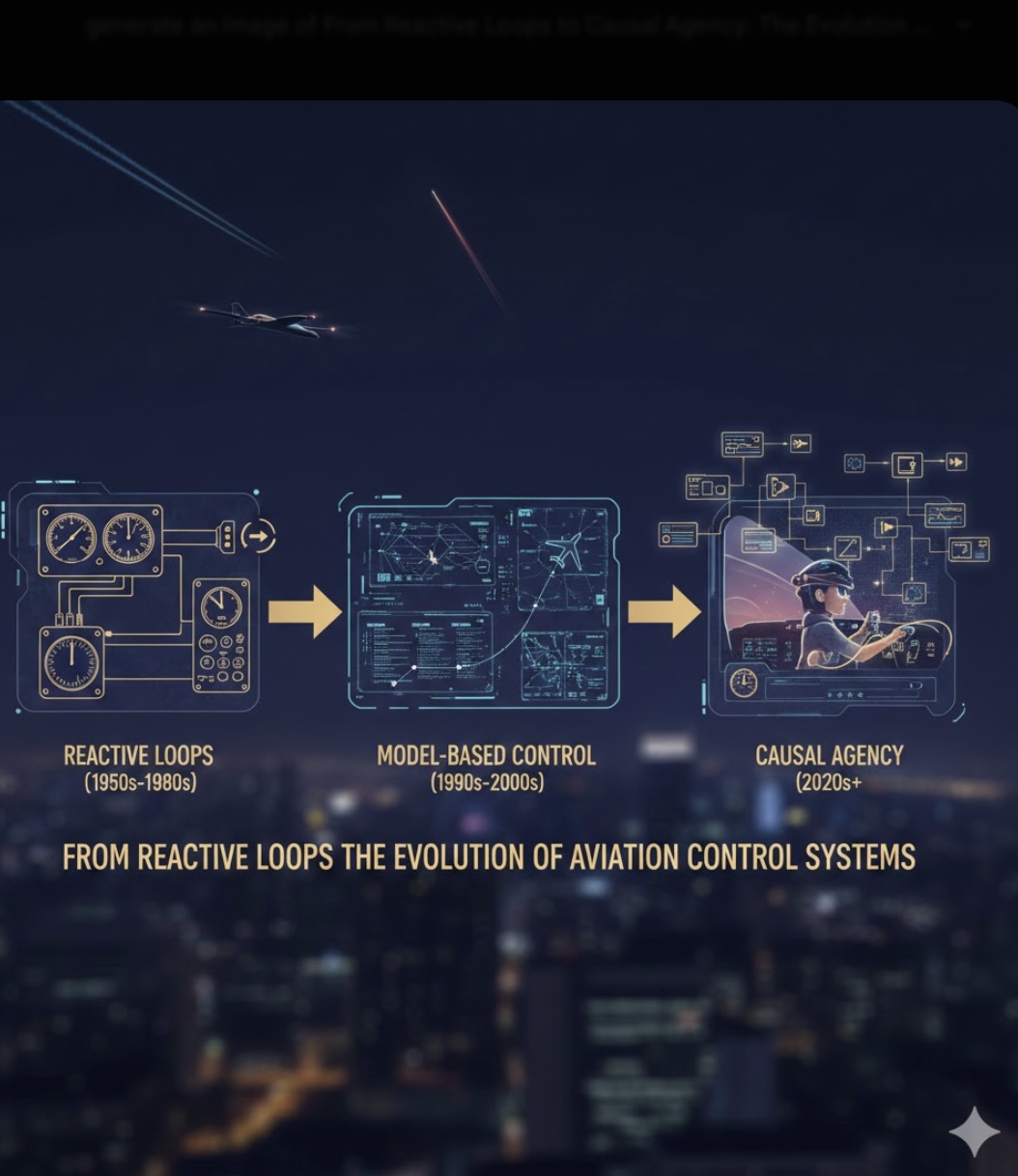

From Reactive Loops to Causal Agency: The Evolution of Aviation Control Systems

From Reactive Loops to Causal Agency: The Evolution of Aviation Control Systems What’s really holding your succession plan back: a lack of successors—or a lack of strategy?

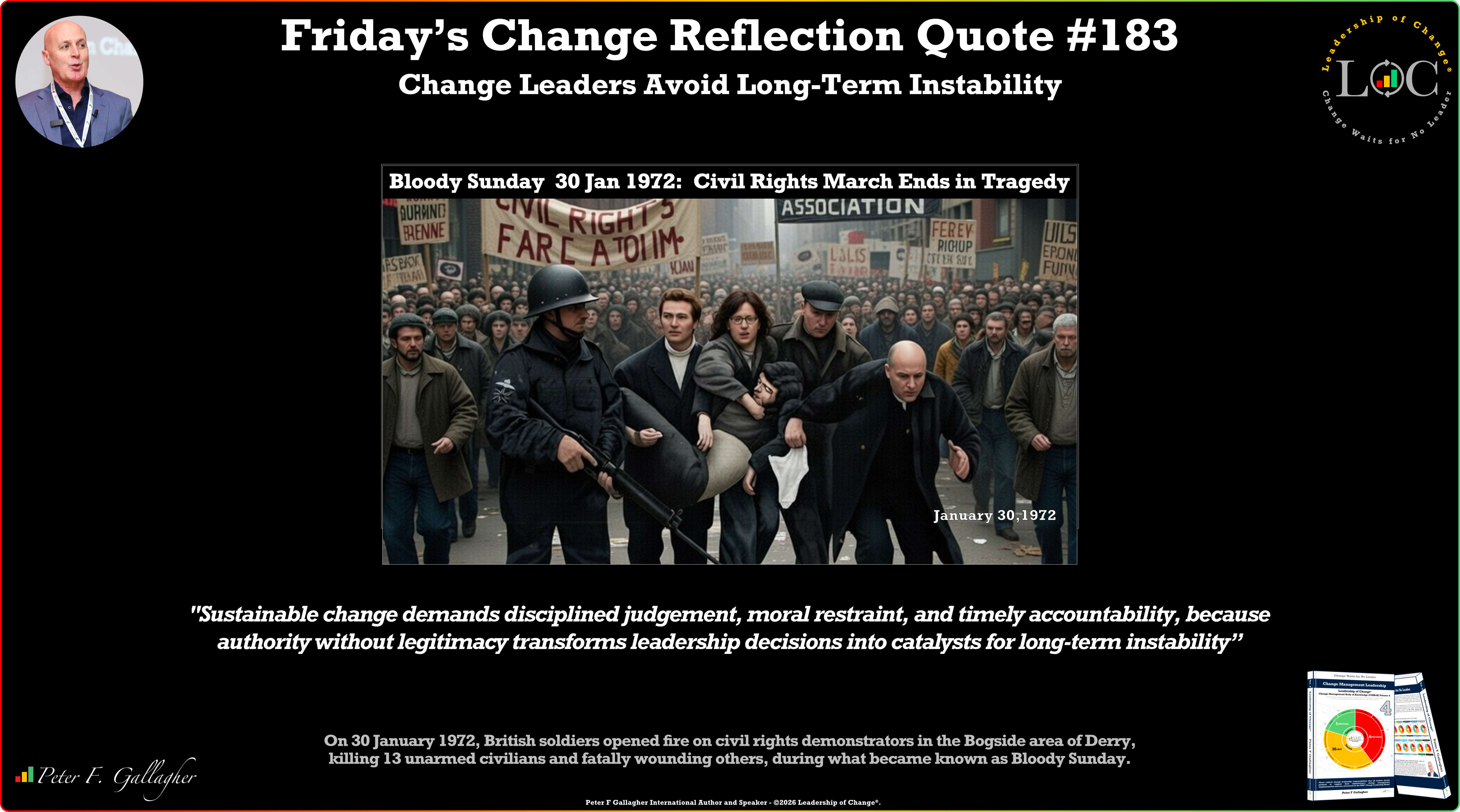

What’s really holding your succession plan back: a lack of successors—or a lack of strategy? Friday’s Change Reflection Quote - Leadership of Change - Change Leaders Avoid Long-Term Instability

Friday’s Change Reflection Quote - Leadership of Change - Change Leaders Avoid Long-Term Instability The Corix Partners Friday Reading List - January 30, 2026

The Corix Partners Friday Reading List - January 30, 2026 Why Long Duration Energy Storage Has Finally Reached Scale

Why Long Duration Energy Storage Has Finally Reached Scale