Feb08

Let’s begin with something playful: a caricature.

The recent surge in AI caricature creation feels like digital fun: a prompt here, a few clicks there, and suddenly we have an image that tries to capture “you” in stylised form. It is delightful, whimsical even, and at first glance seems like pure harmless creativity.

But beneath the cartoon smiles, something subtle and troubling can occur.

One day, former Paralympic swimmer Jessica Smith tried exactly this. She asked an AI model to generate images of herself. These should reflect her real-life appearance, including that she was born without her left arm. Despite carefully written prompts, the AI kept producing images of her with two arms or with prosthetics she never used. When she asked the model why, it replied, in effect, “I don’t have enough examples of people like you in my training data to know how to depict that.”

For Smith – an elite athlete and disability advocate – this wasn’t merely a technical oddity. It was a kind of erasure.

What was supposed to be a caricature tool instead revealed both a blind spot and a deeper truth about how these systems operate.

Large language and image models are, at their core, predictive systems. They don’t understand the world in any human sense; they estimate what is statistically likely given the data they’ve seen.

If a dataset contains overwhelmingly more images of people with two arms than people with one, then (with all else equal) the model will “guess” two arms when creating a new image. This is not prejudice in the conventional moral sense. It is, rather, a kind of regression to the mean: an automatic pull toward what is common and statistically dominant.

This term has a loaded historical lineage. Sir Francis Galton first articulated regression to the mean in the 19th century within the context of heredity and human traits.

Galton was half-cousin to Charles Darwin. But unlike Darwin, who sought to understand evolution as a record of change over time, Galton looked to apply the principle of natural selection to contemporary society. His belief that society could be “improved” by encouraging the reproduction of those with desirable traits, and discouraging that of others, made him the founder of eugenics.

Using it here is not to equate AI with that dark history, but to acknowledge a shared logic: in both cases, deviation from the average gets smoothed toward the centre. This smoothing can have real consequences, even when there is no intent to harm.

Models built on massive datasets implicitly learn the average human first and foremost. Outlier identities that are under-represented in source data become harder for them to reproduce faithfully.

In Smith’s case, multiple attempts yielded images where her limb difference was “fixed,” because the model’s internal representation simply had too few examples of people without bilateral limbs. Only after further updates to the system – in part prompted by public reporting – was it eventually able to depict her accurately.

This example illustrates a broader dynamic:

This is not only about images. Language models trained on text corpora can, for instance, reinforce dominant narratives about gender, culture, or ability if the diversity of voices in their training set is limited. They predict words and images based on patterns in the data they’ve seen. But those patterns are not neutral reflections of humanity; they are historical aggregates of what is most represented.

The resulting outputs can silently privilege “average” experiences and marginalise others. This is not through malice or overt intention, but through the very logic that makes these systems work.

None of this implies that AI is inherently oppressive. Rather, it is a mirror that reflects the statistical shape of its sources.

However, mirrors are imperfect teachers. If the reflection defaults to the familiar, we risk losing sight of the rich, nuanced and often messy contours that make each human story unique.

The question then becomes not whether AI can represent diversity, but whether we build it in such a way that it learns to see nuance as a first principle, not an exception. This requires data that is richer, yes, but also design processes that foreground the voices and experiences of those historically left out.

In other words, intelligence trained on the average will inherently struggle with the margin unless we deliberately teach it otherwise.

If we are not intentionally designing for inclusion then we are unintentionally designing for exclusion.

Framed this way, the concern is not that we are witnessing some deliberate form of digital eugenics, but that systems optimised for efficiency and scale can quietly inherit the same blind spots that once accompanied earlier attempts to classify, rank, and standardise human difference.

When this artificial intelligence is trained primarily on the average, individuality statistically fades.

And perhaps that is the deeper lesson here: our tools will reflect what we feed into them. If we wish to see a world that honours individuality, then our creations – even playful caricatures – must learn not just the mean, but the full tapestry of what it means to be human.

BBC News. (2025, October 14). AI couldn’t picture a woman like me — until now. https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/articles/cj07ley3jnpo

Smith, J. (2025, June 7). When AI erased my disability. TIME. https://time.com/7291170/ai-erased-my-disability-essay/

Sum, C. M., Alharbi, R., Spektor, F., Bennett, C. L., Harrington, C. N., Spiel, K., & Williams, R. M. (2022). Dreaming disability justice in HCI. In CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems Extended Abstracts (pp. 1–5). ACM. https://doi.org/10.1145/3491101.3503731

Stiker, H.-J. (1999). A history of disability (W. Sayers, Trans.). University of Michigan Press.

Danny believes that happy bees make tasty honey. With a purposeful culture, strategy and support systems, high performance becomes a side effect.

He is a psychologist, author of Constellation, an accredited coach, and a psychometrician whose work lies at the intersection of leadership, culture and personality, with a focus on individual differences – especially the “dark triad” traits of narcissism, psychopathy, and Machiavellianism.

An expert in culture and leadership dynamics, Danny has been recognised among the Global Top 10 Thought Leaders on Culture and the Top 25 in Leadership and has spent nearly 30-years in contact centre, retail and fintech industries, designing cultures, leadership systems, and strategies in which energy, clarity, and collaboration multiply success.

He is the founder of Firgun, a consultancy whose Hebrew name captures his core motivation: “the genuine, sincere and pure happiness for another person’s accomplishment or experience”, whose clients include Worldpay, M&G Investment Bank, and LEGO.

More articles are available on his website: dannywareham.co.uk/articles

Keywords: AI, AI Ethics, Culture

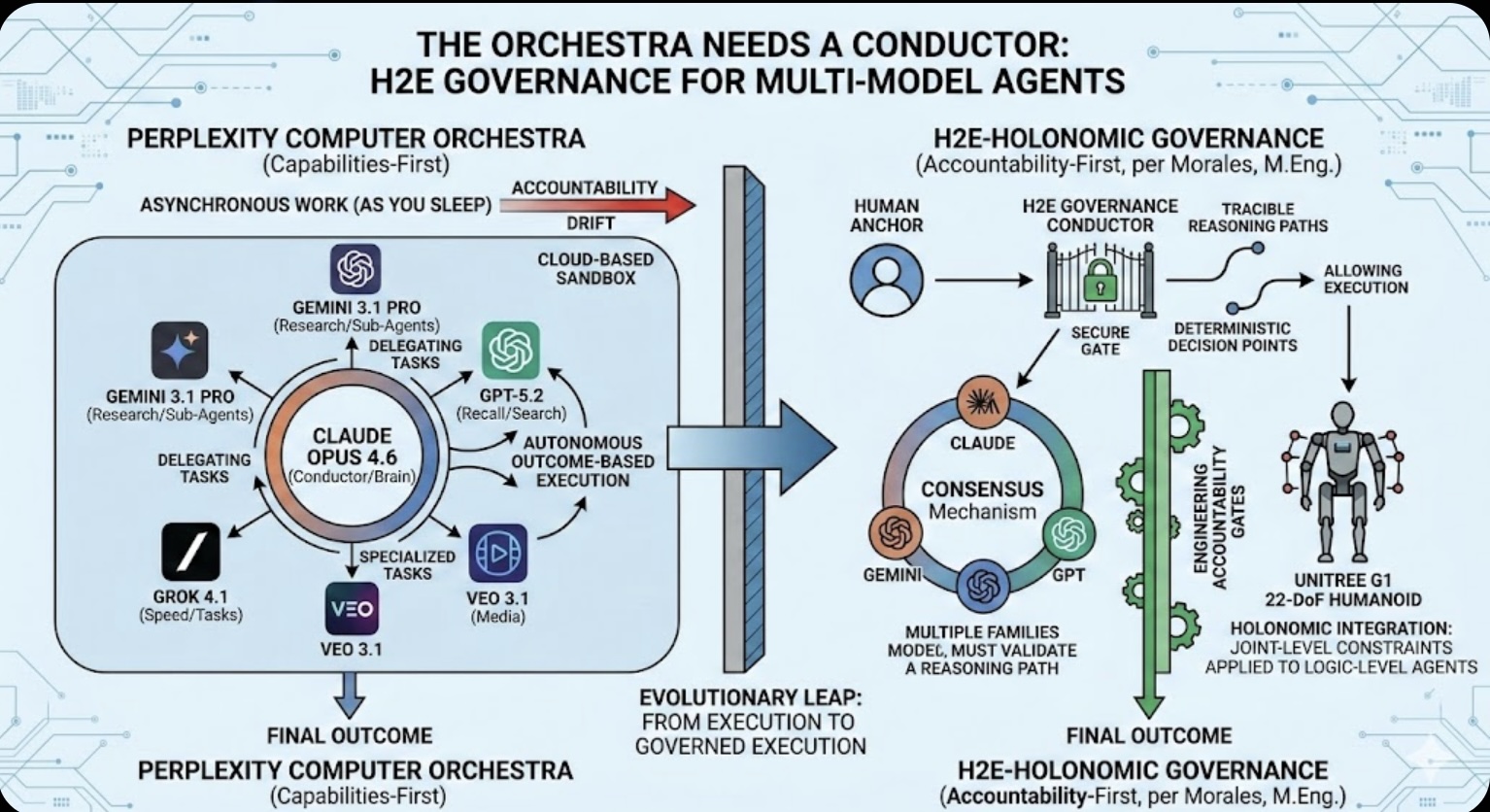

The Orchestra Needs a Conductor: Why Multi-Model Agents Require H2E Governance

The Orchestra Needs a Conductor: Why Multi-Model Agents Require H2E Governance The Role of Memory in Modern-day Business

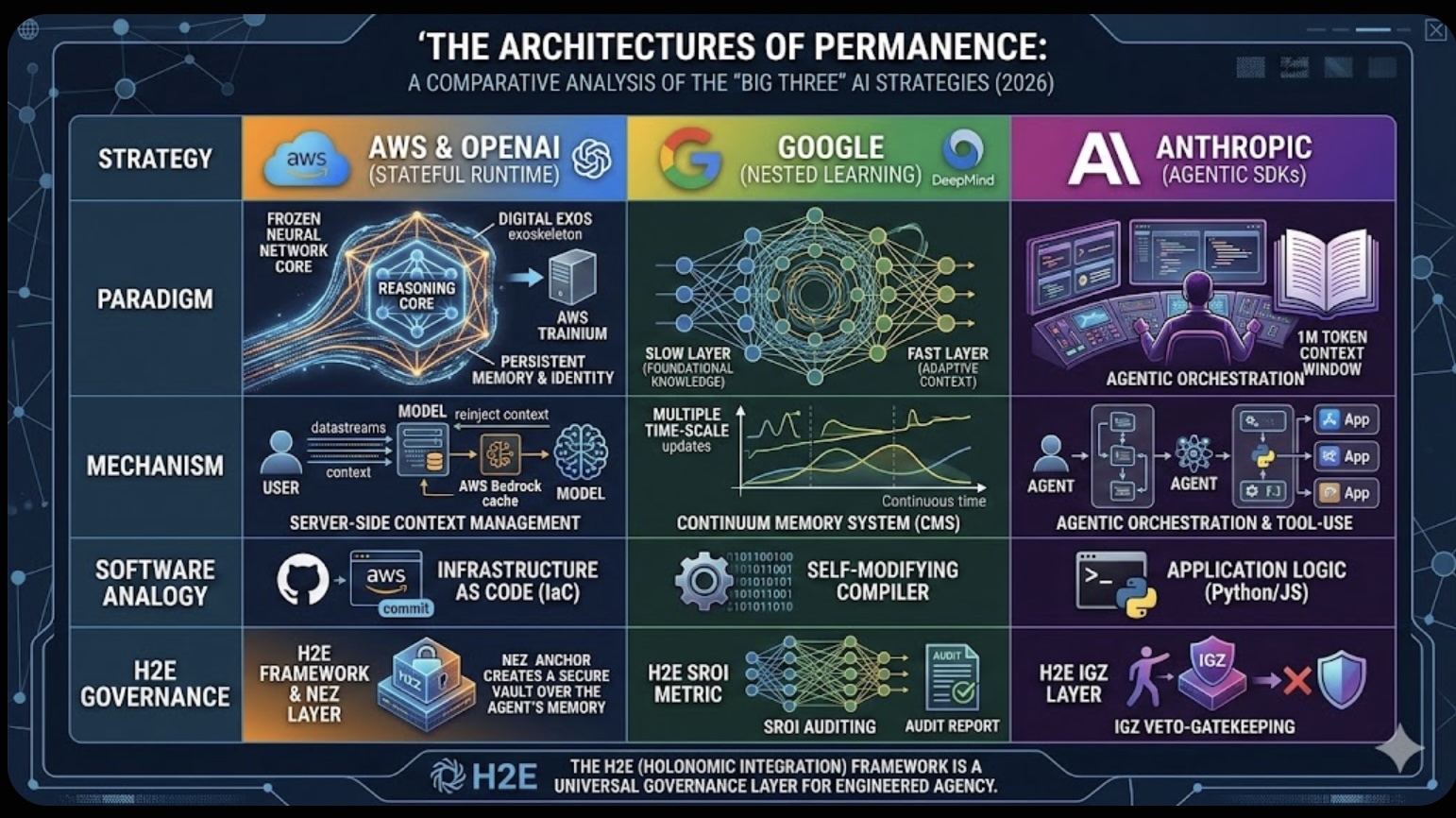

The Role of Memory in Modern-day Business The Architectures of Permanence: A Comparative Analysis of the "Big Three" AI Strategies (2026)

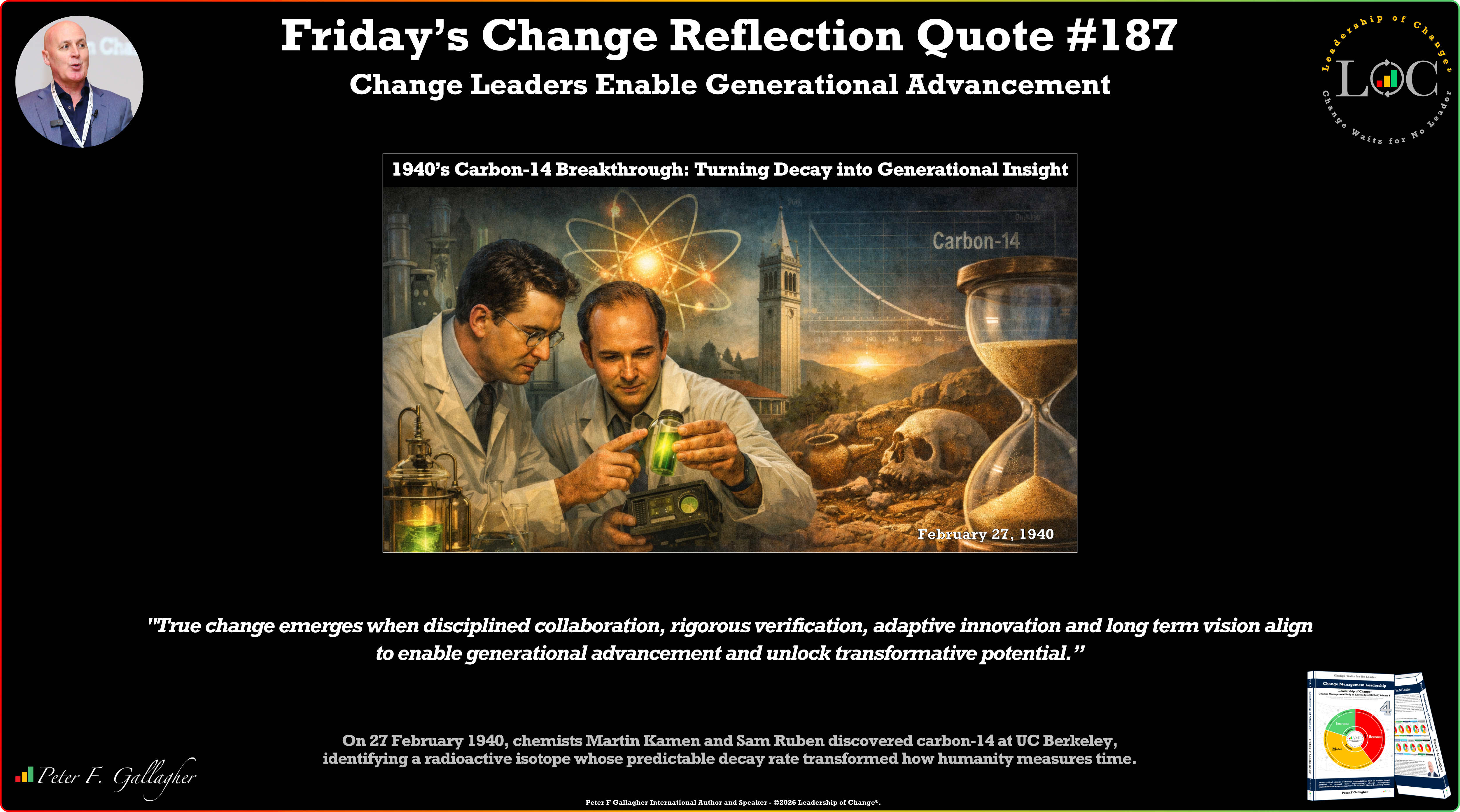

The Architectures of Permanence: A Comparative Analysis of the "Big Three" AI Strategies (2026) Friday’s Change Reflection Quote - Leadership of Change - Change Leaders Enable Generational Advancement

Friday’s Change Reflection Quote - Leadership of Change - Change Leaders Enable Generational Advancement The Corix Partners Friday Reading List - February 27, 2026

The Corix Partners Friday Reading List - February 27, 2026