Jan14

Every organisation has a choice, even if it does not realise it. You can decide to design the future you want to operate in, or you can wait for that future to arrive and then scramble to cope with it. In boardrooms and planning meetings across the country, that choice is being made every day, usually by default rather than by design. When planning becomes reactive, leadership surrenders control to events. When it becomes proactive, leadership regains the initiative and starts to shape outcomes rather than merely respond to them.

Today, the way organisations plan has become a defining source of competitive advantage. Too many leadership teams still run their businesses through the rear-view mirror, reacting to yesterday’s sales, last month’s shortages or last quarter’s financials. That approach may have been workable when markets moved more slowly and product portfolios were stable, but it is now a recipe for margin erosion, customer dissatisfaction and exhausted teams. Proactive planning is not a theoretical ideal; it is a practical discipline that determines whether you are shaping events or being shaped by them.

Reactive planning is deceptively comfortable. It feels safe because it is anchored in facts that have already happened. The data is concrete, the spreadsheets reconcile, and everyone can point to a problem that is visible. The difficulty is that by the time a problem is visible, it has already done its damage. A stock-out has already lost you sales, excess inventory has already tied up working capital, an expediting fee has already eaten into profit. When leaders run their planning cycle on lagging indicators, they institutionalise firefighting as a way of life. People become heroes for fixing crises rather than for preventing them, and the organisation slowly normalises waste.

Proactive planning turns that logic on its head; instead of asking what went wrong, it asks what is likely to go wrong and what we can do now to reduce the impact. That shift is not simply a change in tools; it is a change in mindset. It requires leaders to be comfortable with probabilities rather than certainties and to make decisions on imperfect information. In my years working across global supply chains, I have seen that the companies that thrive are not those with the most detailed history but those with the clearest view of the future they are trying to create.

At its heart, proactive planning is about anticipation. It uses forward-looking demand signals, market intelligence, customer behaviour and scenario modelling to create a range of plausible futures. Instead of producing a single forecast that everyone pretends is accurate, it builds a planning envelope that reflects uncertainty. That allows organisations to put contingency measures in place before they are needed. Capacity can be flexed, suppliers can be aligned, and inventory policies can be set to protect service without bloating stock. When disruption arrives, and it always does, the organisation is not scrambling; it is executing a plan it has already considered.

There is also a deeply human dimension to this; reactive organisations create chronic stress. Teams live in a permanent state of urgency, constantly reprioritising and working late to recover from the latest surprise; that erodes morale, drives attrition and ultimately undermines performance. Proactive planning creates psychological safety, when people know that risks have been identified and options have been prepared, they can focus on doing excellent work rather than simply surviving the next crisis. In leadership terms, it moves the culture from anxiety to confidence.

Financially, the difference is just as stark. Reactive planning tends to be expensive. It drives premium freight, overtime, write-offs and lost sales; these costs are rarely visible in a single line item, but they quietly destroy value across the P and L. Proactive planning, by contrast, allows trade-offs to be made deliberately. You might decide to hold a little more stock in one category to protect a strategic customer, or to accept a longer lead time in another to reduce working capital. Those are conscious, strategic choices rather than panicked reactions, and over time they compound into superior returns.

Technology now makes proactive planning not only possible but unavoidable. Advanced forecasting, demand sensing, scenario analysis and optimisation tools give leaders the ability to see several moves ahead; however, technology alone is not enough. I have seen world-class systems implemented into organisations that still behave reactively because the leadership team continues to manage by exception and anecdote. Proactive planning requires governance, cross-functional alignment and the discipline to stick to the plan even when the noise of the day is loud.

This is a leadership issue; leaders set the tempo of the organisation. When they demand instant answers to yesterday’s problems, they encourage reactive behaviour. When they ask thoughtful questions about tomorrow’s risks and opportunities, they create space for proactive thinking. In a volatile world, the temptation to retreat into short-termism is strong, but it is precisely in such times that long-term, forward-looking planning becomes most valuable.

Proactive planning does not eliminate uncertainty, but it transforms how you live with it. It replaces surprise with preparedness, chaos with coherence and stress with stewardship. For organisations that want to serve their customers well, protect their people and build sustainable performance, there is really only one credible choice. You can either spend your time reacting to a future that keeps ambushing you, or you can invest in shaping a future that you are ready to meet.

By David Food

Keywords: Leadership, Management, Supply Chain

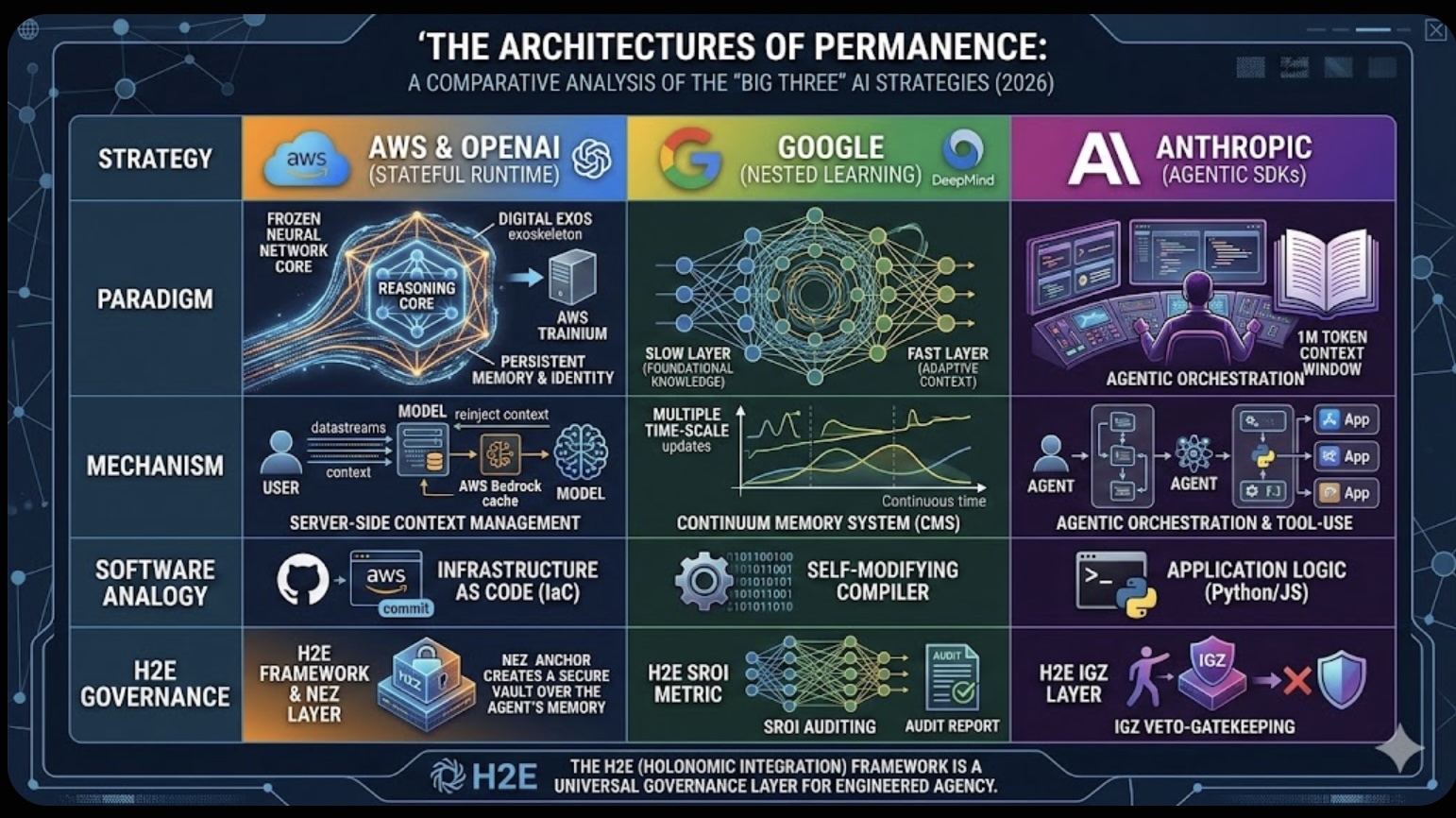

The Architectures of Permanence: A Comparative Analysis of the "Big Three" AI Strategies (2026)

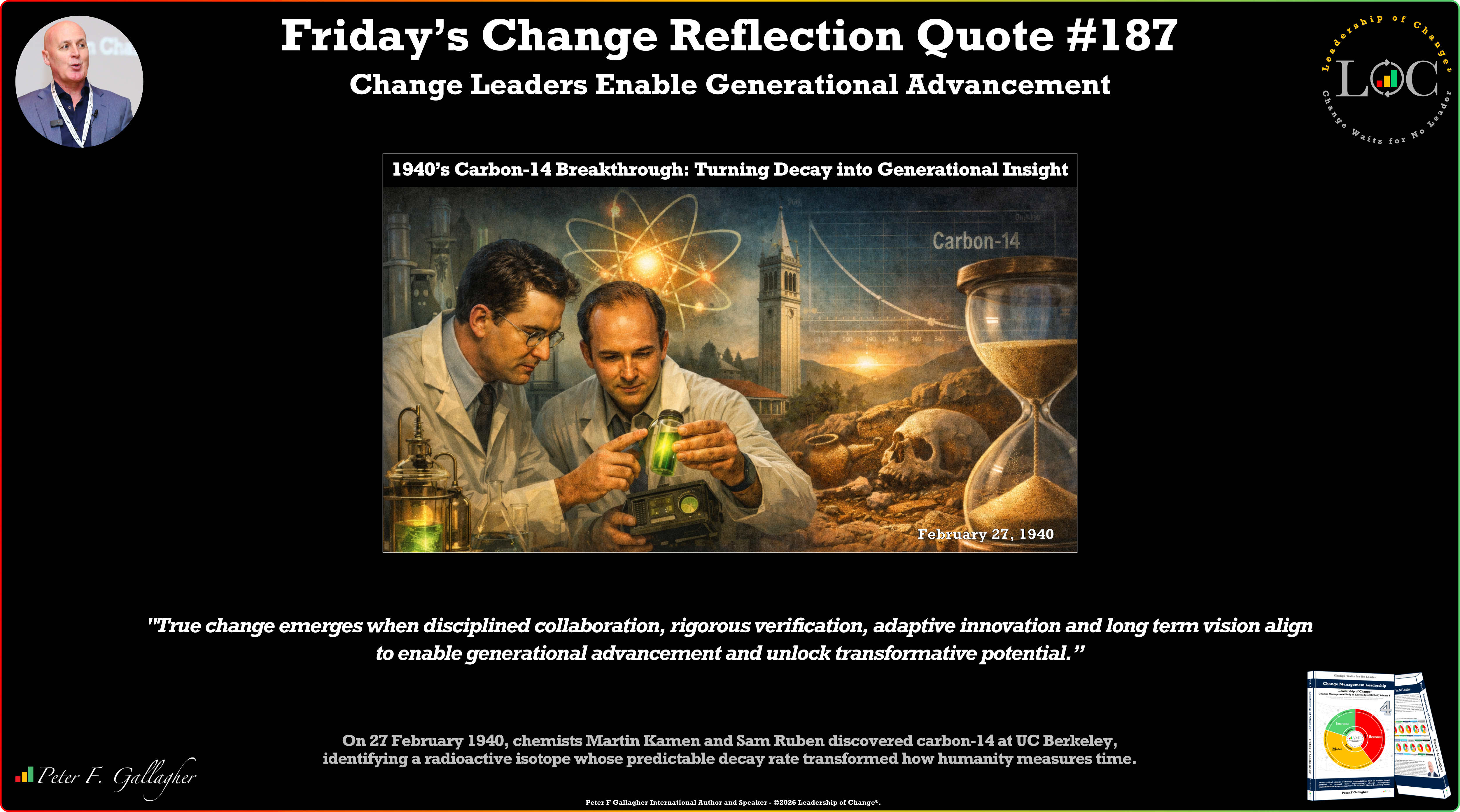

The Architectures of Permanence: A Comparative Analysis of the "Big Three" AI Strategies (2026) Friday’s Change Reflection Quote - Leadership of Change - Change Leaders Enable Generational Advancement

Friday’s Change Reflection Quote - Leadership of Change - Change Leaders Enable Generational Advancement The Corix Partners Friday Reading List - February 27, 2026

The Corix Partners Friday Reading List - February 27, 2026 What Leaders Should Be Losing Sleep Over (But Aren’t)

What Leaders Should Be Losing Sleep Over (But Aren’t) Energy System Resilience: Lessons Europe Must Learn from Ukraine

Energy System Resilience: Lessons Europe Must Learn from Ukraine